If you’re hearing echoes of The Sound of Music in my subtitle, that’s only appropriate, because I have a mountain to climb.

As Christopher Haigh says in his 2001 preface to the new edition of his Elizabeth I, originally published in 1988:

Elizabeth I has been a popular woman. In the twentieth century almost a hundred biographies of her were published. Just a few of them have become classics, most obviously J. E. Neale’s: it was published in 1934, and is probably still the best – which is quite a criticism of those that came after. But it is hard to write a good biography of Elizabeth.

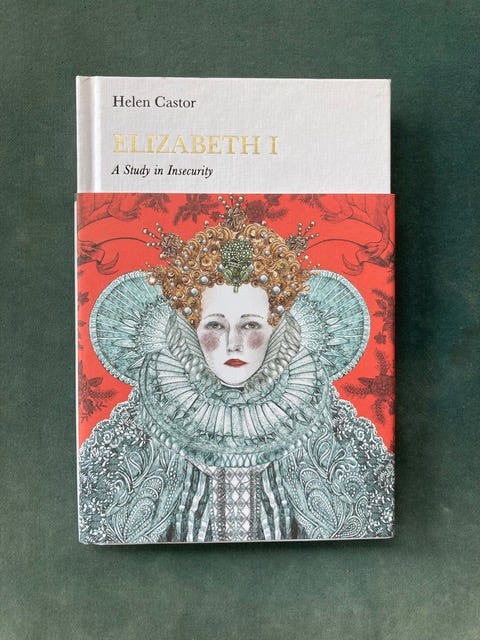

It certainly is; but I’m not going to let that stop me trying. Or trying again, given that I’ve already written a very short book about her in the Penguin Monarchs series. That – at just 25,000 words, the allotted space for every monarch, no matter how long or eventful their reign – was intended as something like an essay: a thesis about a life. Now I’m writing at full length, about her whole life, her whole person.

Elizabeth was an intimidating presence to her subjects, and she remains intimidating as a subject. As Haigh goes on, ‘It is difficult to find the real Elizabeth, because she was always putting on some sort of act’.

For me, there’s the further layer that she’s where my own history in History began: with Jean Plaidy’s The Young Elizabeth, first published in 1961, by which I was transfixed as a small child in the early 1970s.

But difficulty brings challenge, and excitement – and a blank page is both challenging and exciting. So I’ve been thinking about beginnings.

They matter. They matter in terms of storytelling: ‘Once upon a time…’.

And they matter to me because I write in order, sentence by sentence, from the beginning to the end. Finding the right place to start therefore means I can go on.

I’ve sometimes begun with a narrative moment. The opening scene of She-Wolves – the death of fifteen-year-old Edward VI – was what first gave me the idea for the whole book: in contemplating the terrible loneliness of this orphaned king, I’d begun to think about his wider family, and the fact that every single one of the possible heirs to his throne was a woman. Joan of Arc opens with the battle of Agincourt – or, in my version, Azincourt – to establish that the book would tell the story of the war in which Joan made her meteoric intervention; that it would be told from the perspective of a defeated and divided France; and that, in Henry V, England too had a leader convinced that he was on a mission from God.

In The Eagle and the Hart I began with a proposition: that Richard II had always been convinced of his own specialness. That was the idea that allowed me to find a path through his place in his family, his dynasty, his childhood and his future, and to make my first (but not last) comparison with the other subject of the book, his cousin Henry of Bolingbroke.

So where to start with Elizabeth?

This week, I picked some books about her from my shelves to see how they tackle the problem of beginning. Below, you’ll find the first two sentences from each volume in this unscientific sample of ten books published between 1934 (J. E. Neale, the classic cited by Christopher Haigh) and 2018 (my Penguin Monarch). Eight are written for adult readers, two for children; one (Plaidy’s Young Elizabeth) is historical fiction.

For now, I haven’t opened books by anyone I know (apart from me, and how well do any of us know ourselves?), partly in the hope that anyone who has a more recent favourite might share it in the comments – I’d love to know what you think.

Here they are, in chronological order.

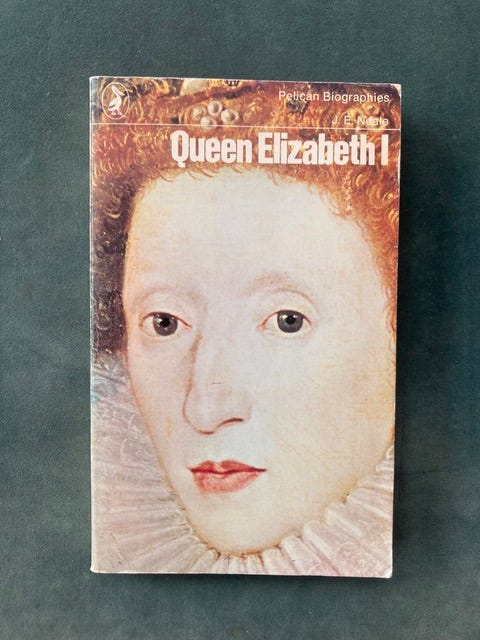

J.E. Neale, Queen Elizabeth, 1934:

On Sunday, 7 September 1533, between the hours of three and four in the afternoon, Anne Boleyn gave birth to a child at the pleasant river-palace of Greenwich. Its destiny was bound up with accidents of State, which none could then foretell: but this at least might have been discerned, that the birth was a symbol of the most momentous revolution in the history of the country.

A life begins with a birth. And a classic begins with a confident statement: the English reformation was, at the time it happened, the most momentous revolution in English history. Discuss?

Edith Sitwell, Fanfare for Elizabeth, 1946:

This is England, this is the Happy Isle; it is the year 1533 and we are on our way to the country palace of the King – a giant with a beard of gold and a will of iron. . . . ‘If a lion knew his strength,’ said Sir Thomas More to Cromwell, of his master, ‘it were hard to rule him.’

What an opening... We’re on the way to a birth, with echoes of Shakespeare’s sceptred isle and happy breed of men, via the leonine person of the baby’s father and his echoes of what Elizabeth herself would become. The ellipsis in these lines is Sitwell’s. What does it signify, I wonder?

Fanfare for Elizabeth is Sitwell’s ‘Young Elizabeth’, taking its subject up to the age of 15. She told the rest of the story in The Queens and the Hive in 1962.

Elizabeth Jenkins, Elizabeth the Great, 1958:

thinks we should all read more Elizabeth Jenkins, and I think he’s right. This first sentence is a thing of beauty. It’s gorgeously weighed and weighted; it sets thoughts racing – was anyone more remarkable? – and brings to mind the extraordinary portraits of the teenage Elizabeth and Edward – pale and close-lipped, both – by William Scrots. I reopened this book recently, decades after reading it, and realised the opening had stayed with me all that time.When Henry VIII died in January 1547, the most remarkable beings left in the realm were three pale and close-lipped children. One was his daughter Elizabeth by his second wife Ann Boleyn, another was his son Edward by his third wife Jane Seymour, the third was his great-niece Jane, granddaughter of his sister Mary and eldest child of Lord Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset.

L. du Garde Peach, The Story of the First Queen Elizabeth, 1958:

On a fine Sunday in the late summer of the year 1533, more than four hundred years ago, a baby girl was born in a palace at Greenwich on the River Thames, between London and the sea. Her parents were the King and Queen of England, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, the daughter of an Alderman of the City of London.

There’s so much to love about the Ladybird Elizabeth, not least this attempt to make Anne Boleyn – and presumably therefore by extension Elizabeth too – a scion of the solidly mercantile English middle class. On the same page, her mother’s fate and her father’s subsequent matrimonial career are passed over in tactful silence. This is that rare book where Henry appears without his six wives.

Jean Plaidy, The Young Elizabeth, 1961:

‘Wake up! Wake up! The time has come now.’ The girl in the bed opened her eyes and stared at the woman who was bending over her.

For those who don’t know, four-year-old Elizabeth is being woken in her curtained bed at Hampton Court Palace to take her ceremonial part in the christening of her baby brother Edward. For those who do, I suspect you can still see William Randel’s line-drawing as clearly as I can.

Neville Williams, Elizabeth, Queen of England, 1967:

Like Eve, it had all begun with an apple. The courtiers who had gathered in the whispering gallery of politics, outside Anne Boleyn’s chamber in Whitehall Palace, one February morning in 1533 first heard the news.

Did you know that Anne reported ‘such a violent desire to eat apples, as she had never felt before’ at what turned out to be the start of her pregnancy? Neville Williams, who became Deputy Keeper of Public Records at the Public Record Office not long after this book was published, is here – brilliantly – to tell us.

Christopher Haigh, Elizabeth I, 1988, reissued in a new edition 2001:

On Sunday 30 April 1536, little Elizabeth Tudor was clutched in her mother’s arms as her parents argued through a window at Greenwich Palace. The child, two-and-a-half years old, was lifted up by Queen Anne to seek sympathy from an angry King Henry VIII: the pleadings failed.

Haigh’s book, he says sternly in his preface, ‘is not a biography of Elizabeth I – there are too many of them already’. All the same, he starts with a vignette from the desperate end of her parents’ marriage. The drama may be familiar, but it’s hard to ignore.

Christopher Hibbert, The Virgin Queen: The Personal History of Elizabeth I, 1990:

London was being prepared for ‘a great and glorious event’. The fronts of houses had been washed and their windows cleaned; coats of arms, heraldic beasts and shop signs had been repainted, flags and banners unfurled, state barges and other river craft polished and gilded, railings garlanded.

The scene is colourfully set, but misdirection is in train. We’re expecting Elizabeth’s birth; instead, by the end of the paragraph we find ourselves at the wedding of Henry VIII’s elder brother Arthur to Catherine of Aragon, the event that paved the long and tortuous way for Henry’s marriage to Elizabeth’s mother.

(Three sentences further on, Richard II needs to register an architectural protest: the walls of Westminster Hall may be Norman, but its glorious hammerbeam roof, built 300 years later in the 1390s, certainly isn’t.)

Wallace MacCaffrey, Elizabeth I, 1993:

Early in September 1533, the Lord Mayor of London and the other civic dignitaries were bidden to attend a great state ceremony at the royal palace of Greenwich. In the church of the Friars Minors on Wednesday, 10 September, the three-day-old princess Elizabeth, first-born child of Henry VIII’s second marriage, was to be christened.

Civic dignitaries again, and this time I’m not entirely sure why – unless they’re to be our representatives as we’re ushered into a characteristically brisk, focused and information-packed introduction.

Me, Elizabeth I: A Study in Insecurity, 2018:

On the morning of Friday 19 May 1536, a woman in a grey silk gown climbed a newly built wooden scaffold within the precincts of the Tower of London. She spoke a few words to the large crowd that pressed silently around the platform, then removed her gable headdress and tucked her dark hair into a cap to expose her slender neck.

And, well, here we are: the ‘inciting incident’ for my essay. Anne Boleyn is about to lose her head. I was attempting to see her death with fresh eyes, because hindsight – what I ended up calling the ‘bludgeoning familiarity’ of the story – too easily stops us feeling the visceral shock of the first judicial execution of an English noblewoman, let alone an anointed queen.

I’ll leave you almost – but not quite – where we started: with J. E. Neale, whose Queen Elizabeth, originally written for the four hundredth anniversary of her birth in 1933, had to be renamed Queen Elizabeth I when it was republished in 1952. Neale discussed the change (‘for obvious reasons’) in a prefatory note:

The book was written before such words as ‘ideological’, ‘fifth column’, and ‘cold war’ became current; and it is perhaps as well that they are not there. But the ideas are present, as is the idea of romantic leadership of a nation in peril, because they were present in Elizabethan times. They should make the past more real to us; and the accession of a second Queen Elizabeth in the same year of her age as the first will surely stimulate interest.

Hindsight – we always need to remember – changes everything.

A book about Elizabeth I by Helen Castor. Oh. My. Goodness! I can hardly wait!

A few years ago, I read John Guy’s 2004 biography of Mary Stuart, entitled, “Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart”. I was struck by a comment in Guy’s Acknowledgements section, in which he wrote: “I had no idea when I began that so much fresh material could be found in the archives about a woman who has been the daughter of debate for four centuries. Then, when I steadily began to uncover this material, I felt a sense of elation.”

Rather than rely upon printed primary sources, Guy went back to the original documents, where he was often surprised to find significant discrepancies between the two. He also found that documents had been misfiled, or had apparently disappeared altogether; I say apparently because in the course of Guy's researches a trove of original documents on Mary’s trial and execution suddenly reappeared at an auction after having been missing since the early 18th century.

I had the impression Guy found that, even when historians do consult the original documents, they tend to read only those dealing with particularly notable events in Mary’s life, leaving the rest untouched. I may be entirely wrong about this, but I was left with the vision of bundles of documents tied up with faded red ribbons and wax seals, unopened for over four hundred years, containing who knows what treasures! At the risk of sounding presumptuous, perhaps you could even contact Professor Guy yourself to see what his findings were about Mary and how they might assist you in your own endeavours concerning Elizabeth.

Of course, I’m talking about Mary, Queen of Scots, not Elizabeth I, but it’s difficult not to think—or at least hope—that there are episodes in Gloriana’s reign that still await discovery deep in the archives. But perhaps that’s just wishful thinking on my part.

In any case, I’ve been interested in Elizabethan England ever since as a small boy I watched TV broadcasts of Errol Flynn films such as, “The Sea Hawk” and “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex”. I’ve also gathered a half-dozen or so shelf-loads of books about Elizabeth and her times over the years, and I look forward to adding yours to my collection.